Many families may be beginning to wonder if their children’s school gets out earlier or later than everyone else’s. With summer break on the horizon (some schools are actually already on break), let’s look at summer breaks for Missouri public school districts by the numbers.

*Statistics are based on a self-compiled compilation of calendars. If snows/sick days have shifted the last day of school, they are not accounted for.

**Kairos Academies, Clarksburg C-2, Clarkton C-4, Crocker R-II, Eldon R-I, La Salle Charter School, Mark Twain R-VIII, New York R-IV, Premier Charter School, The Biome, Thornfield R-I, and Union Star R-II are not accounted for.

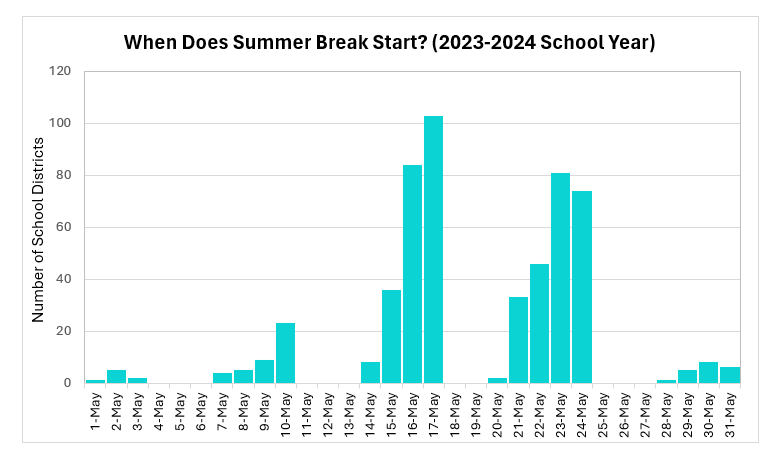

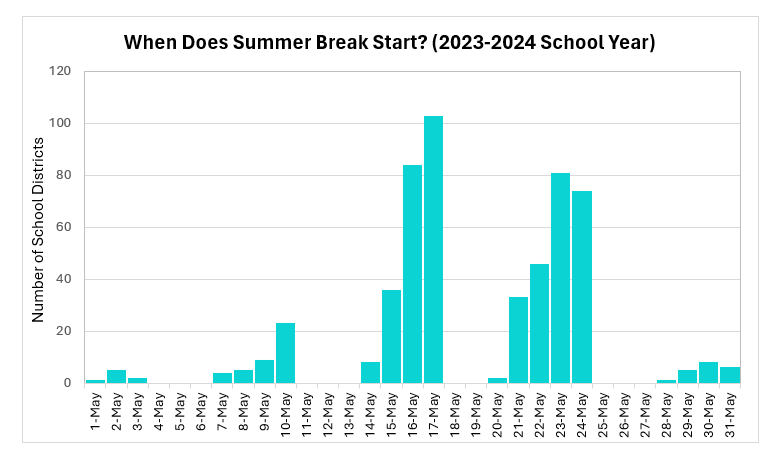

Skyline R-II was the first district to start summer break, on May 1. Hazelwood and Ferguson-Florissant will be among the final districts to go on break on May 31.

Based on the projected last day of class, if you are a St. Louis kid, you are probably getting out later than everyone else. Of the 15 traditional school districts (non-charters using a five-day school week) that end classes May 28 or later, 11 of them are in the St. Louis area. These St. Louis–area schools are Ferguson-Florissant, Hazelwood, Clayton, Ft. Zumwalt, Parkway, Wentzville, Ladue, Maplewood-Richmond Heights, University City, Mehlville, and Riverview Gardens.

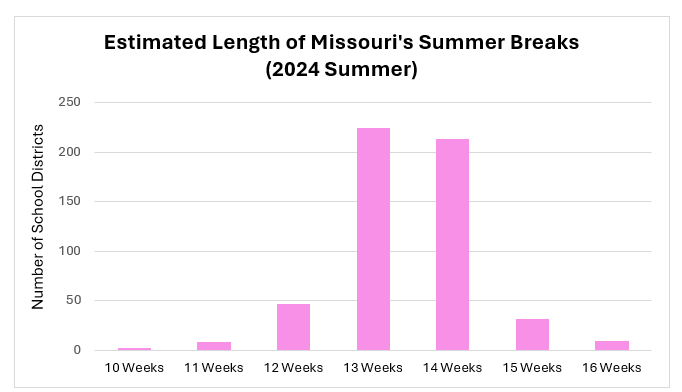

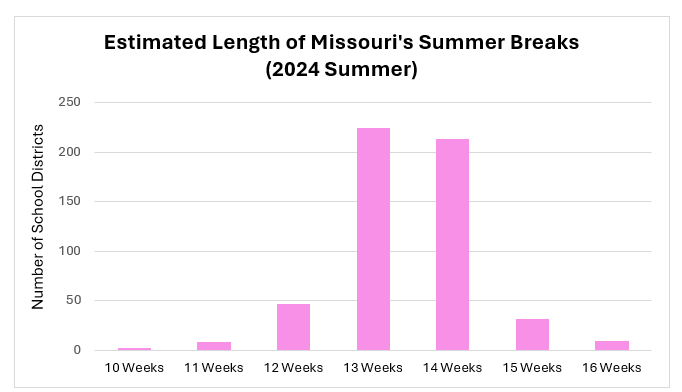

How long do most summer breaks last in Missouri?

*Based on the projected number of days, we rounded the district to the nearest week. For example, a district with an 81-day summer would be coded as “12 weeks.”

**In this estimation we assume districts have the same first day of school as 2023-2024, and then subtracted that number by two. In 2020, Missouri mandated that Missouri public schools’ first day of school cannot be before a certain date. In 2023-2024, it was August 21st. For 2024-2025, it will be August 19th, two days earlier.

As the above figure displays, the average summer break is a little over three months for Missouri students. The shortest summer break is roughly 10 weeks, while the longest is around four months at 16 weeks. The rural districts (enrollment in parentheses) of Fairview R-XI (493), Glenwood R-VIII (218), Howell Valley R-I (209), Junction Hill C-12 (193), and Richards R-V (343) all have nearly four-month summer vacations—with May 2 as their last day of class, and August 21 as their first day of class in 2023–2024.

Interestingly, the districts that have the shortest summer breaks all tend to be St. Louis–area districts, with Ferguson-Florissant and Hazelwood having the shortest breaks. Along with these two, Clayton, Ft. Zumwalt, Parkway C-2, Wentzville, Ladue, University City, Mehlville, Riverview Gardens, Affton, Bayless, Brentwood, Francis Howell, Orchard Farm, Rockwood, and Valley Park all have estimated summer breaks under 90 days.

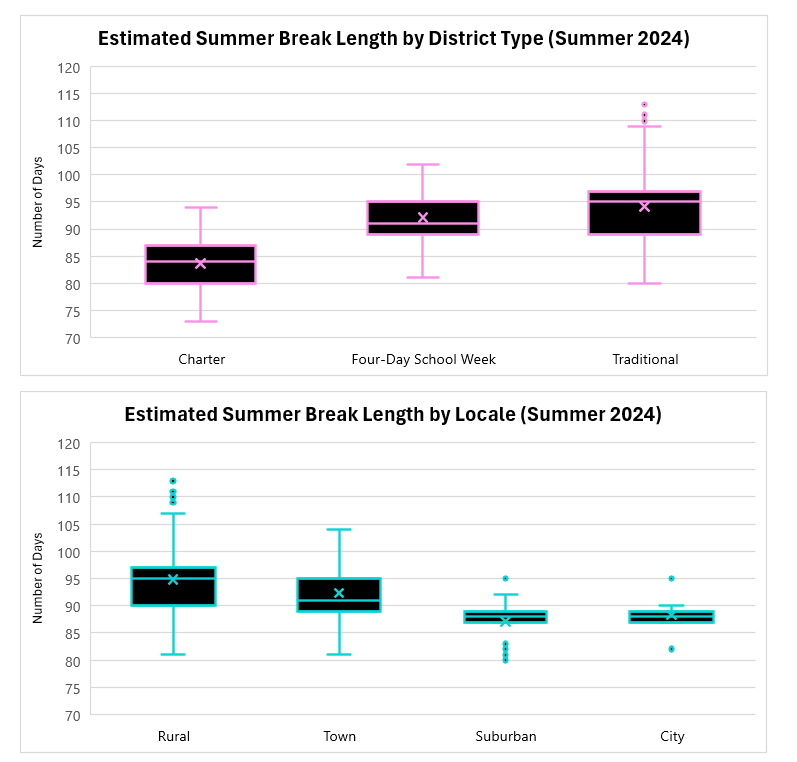

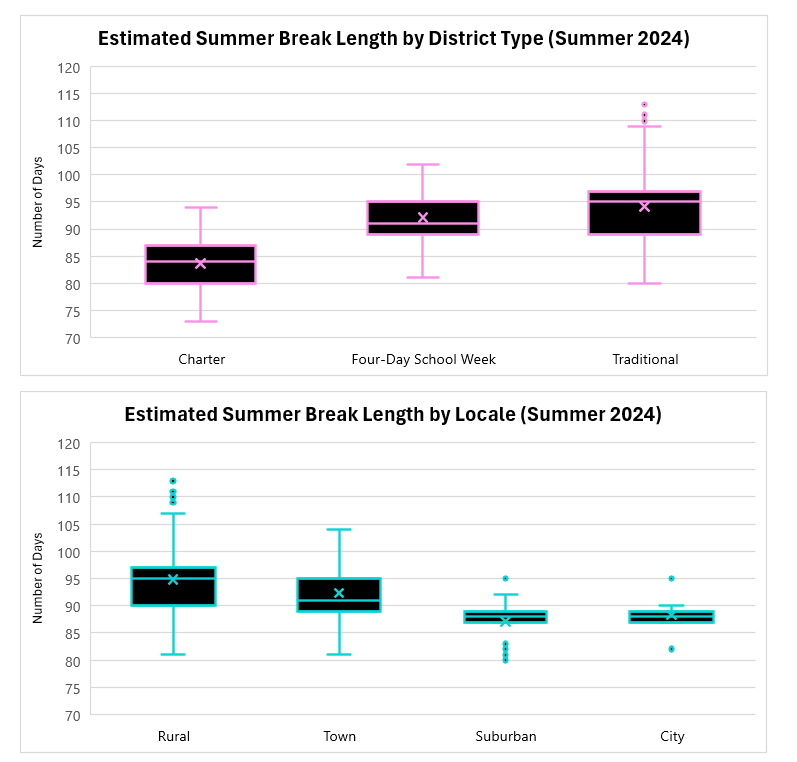

How do these statistics differ amongst various types of schools?

The above figures are known as a box and whisker plot. The vertical line (whiskers) represents the full range, while the box represents the middle 50 percent of responses. Any statistical outliers are noted as dots, the horizontal line is the median, and the “x” is the mean.

As shown, rural schools on average have much longer summer breaks than their suburban and city counterparts. Additionally, most of the longest breaks in the state are rural—of the 50 longest summer breaks in the state, 47 of them are rural districts. While this may be reflective of the bygone days when most rural children worked on farms, Institute analysts have conducted research that found rural high school students may have fewer opportunities and lower rate of college readiness than their suburban counterparts.

Another important takeaway from these figures is the difference in break length between charters and traditional schools. Charter schools have an average (mean) summer break of 84 days, versus 92 for four-day school week districts and 94 days for traditional five-day school week districts. In Missouri, charter schools serve high proportions of disadvantaged students and shorter breaks may be a good use of charter school flexibility.

Do longer summers hurt students? Summer learning loss is a well-documented phenomenon. However, there are debates about the actual extent of achievement loss. Regardless, it is interesting to see the variability across the state and to consider if there could be academic implications.