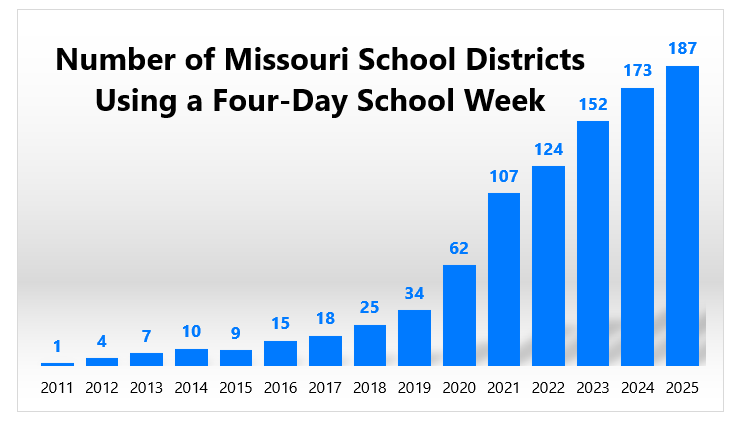

The four-day school week (4dsw) continues to expand rapidly in Missouri. The 4dsw grew from 34 districts in 2018–2019, or 6.5% of all Missouri districts, to 173 districts in 2023–2024, which is about 1 out of 3 districts. In just five years, almost 150 districts made the switch to a 4dsw.

Official numbers from the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) have not been yet released for the 2024–2025 school year. However, according to my own compilation, the 4dsw has continued to grow, as now 187 Missouri public school districts operate on a 4dsw schedule, out of 516 total districts.

My colleague James Shuls and I addressed a wide variety of concerns with the growing 4dsw on academic achievement, district finances, teacher retention, parental preferences, demographics, and learning time effects in a recent series of papers. These include a systematic literature review, a survey, and a descriptive analysis.

In brief summary, we found the 4dsw typically lowers academic achievement and instructional time, while also showing mixed and inconclusive effects on district finances and teacher retention. Overall, there is little evidence to suggest switching to a 4dsw has a lot of benefits, so districts should be cautious when considering the switch.

The Missouri Legislature took aim at the 4dsw in the recent Senate Bill (SB) 727 (SB 727). This law requires larger districts to acquire parental approval before switching to a 4dsw, and also creates an aid bonus for districts that have 169 days of school or more (which essentially means you must be a 5dsw to receive it). As the below figure shows, the prospect of these measures coming fully into effect in 2026-2027 did not seem to stop 4dsw growth going into the 2024–2025 school year.

In rural Missouri, the 4dsw is nearing the majority, as 47% of rural districts are now using the 4dsw. In 2024-2025, every new district which made the switch to a 4dsw was a rural district. Still no city districts have adopted the measure, and no other suburban district joined the Independence 30 School District in making the switch—although some have discussed it.

It will be interesting to see how the continued growth of the 4dsw affects our state. Is there a proximity effect—do districts near each other feel more pressured to switch? There is a dearth of information on the 4dsw. Shouldn’t Missouri districts proceed with caution when considering a switch?