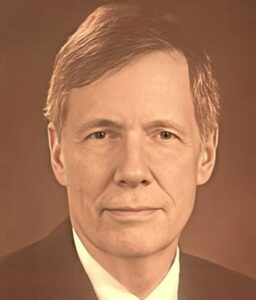

January 10, 1952 – November 11, 2025

It is with deep sadness that I share the news of the passing of Joseph Forshaw IV, longtime member of the Show-Me Institute’s Board of Directors, former treasurer, and past chairman of the board.

Joe was more than a board member to us. He was a steadfast champion of the Show-Me Institute’s mission, a source of wisdom and clarity, an incredible mentor, and a man whose integrity and good humor strengthened everyone around him.

A lifelong St. Louisan, Joe brought to our organization the same qualities that defined his life: intellectual curiosity, disciplined thinking, and generosity of spirit. Before joining the Show-Me Institute, he served for 30 years as president of Forshaw of St. Louis, the family business founded in 1871. His deep understanding of entrepreneurship and free enterprise made him an invaluable voice on our board and a trusted adviser to our team.

Joe served with humility and conviction, and he cared deeply about Missouri’s future. He was an extraordinary mentor to many of us, always ready to offer thoughtful counsel, encouragement, and the perspective that comes from a life well lived. Whether asking the question no one else had considered or reminding us to stay focused on the people we serve, he did so with grace, steadiness, and genuine kindness. His presence made our work better, and his passion for ideas strengthened the entire organization.

I extend my heartfelt condolences to his beloved wife, Liza; their children Sr. Maria Battista, Juliet, and J. Alexander; his grandson Aidan; and the entire Forshaw family. Joe’s leadership, generosity, and friendship will be deeply missed.

Details about visitation and services can be found here.