There are so many things that go well together during the Christmas season. Faith and family, sweet potatoes and those little marshmallows on top, and (less enjoyably) my fantasy football team and a tragic playoff loss.

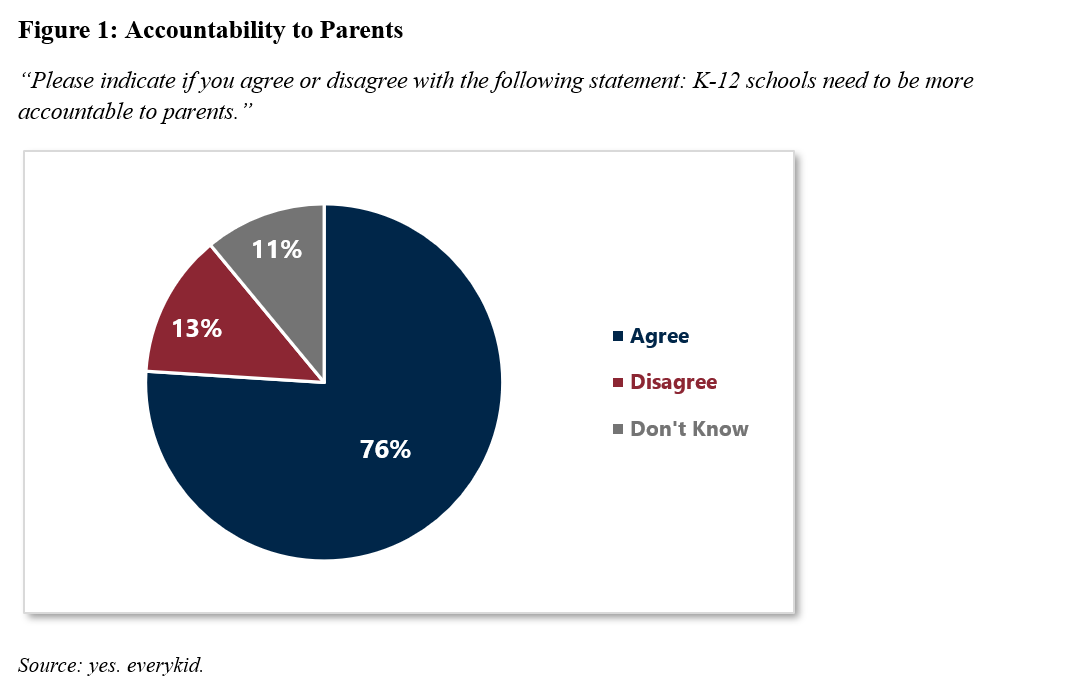

Jokes aside, I came across a recent poll from the yes. every kid. foundation that reminded me of a vital pairing for holding education systems accountable: understandable information and comparable information.

The poll is nationwide, but the results apply to Missouri. Parents want to hold schools accountable, but they need high-quality information to engage.

Our annual Blueprint has consistently emphasized the importance of building informational resources that are both understandable and comparable. Missouri provides some data, but there is no central, user-friendly landing place where parents can easily access and evaluate information about the quality of their children’s schools.

For instance, this data dashboard from DESE reports a number of understandable statistics for the year, but you cannot compare districts to each other. Some DESE sources are difficult to decipher and navigate altogether. And if a parent truly wants to compare districts and years, they will need to break out their Microsoft Excel skills.

Using DESE’s dashboard, a parent can see that 58 percent of Parkway C-2 students scored proficient or advanced in mathematics on the Missouri Assessment Program. But is that good? Isn’t 70 percent usually a passing score? How does it compare to last year? How does it compare to other districts across the state? Should a parent be concerned, or encouraged?

These are all important questions, and sadly, the answers require a lot of digging.

Thankfully, parents can find the answers to these questions on our own website, MOSchoolRankings.org.

There, Parkway C-2 is ranked as one of the better districts in our state: 133 out of 551 overall. In fact, its math score is the 37th best in the state. But it’s not all peachy in Parkway, as its low-income math scores ranked 378th in the state, and the overall mathematics score declined from the prior year. These statistics give meaningful context for parents to more accurately hold schools accountable.

Our website serves as a valuable resource for the state, but DESE ought to provide a similar tool—one that is even more comprehensive and accessible—using the state’s greater manpower and authority.

Taken together, survey data and practical experience point to the same conclusion: Missouri’s education system needs to be more accountable to parents. Achieving that goal requires creating resources that are both understandable and comparable.