Last year, voters in the City of St. Louis approved a rather ambiguous half-percent sales tax hike, Proposition 1. Sixty percent of revenues from that tax, which totaled $23.9 million this past fiscal year (p. 49), are slated to fund a north–south MetroLink expansion.

But who knows what city taxpayers will end up getting for their “investment?”

Taxpayers likely won’t get the 17-mile route they were presented last year. After more than a year of study, it was recently announced that the first phase of expansion will run some 9 miles, roughly from Chippewa St. to the NGA site north of downtown, and will cost $700 million. The project is also totally dependent on federal funding, which is a big if at this point, and will begin operations, best case scenario, in a decade.

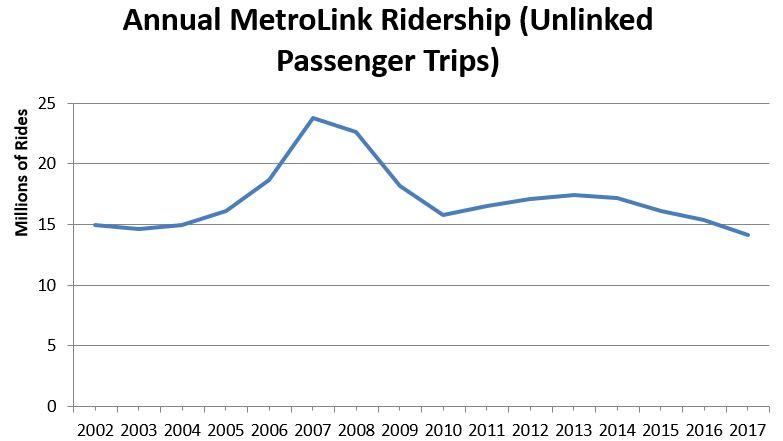

It’s also unclear whether the expansion will get St. Louisans out of their cars. While consultants project the line will carry some 9,200 riders a day, my colleague Joe Miller has pointed out that it runs through neighborhoods with relatively low population density—density about a quarter of what’s needed for light-rail to be successful. Also, overall MetroLink ridership is trending downward; not only has it lost 3.9 million annual rides since 2014, but the rail system carries fewer passengers than it did prior to the 2006 Shrewsbury expansion. And crime on and around MetroLink trains has, according to Metro, contributed to an 11% decline in ridership since last year. While I don’t doubt that an expanded system will (at least initially) carry more passengers, experience—and more than 15 years’ worth of data—suggest we shouldn’t get our hopes up.

Source: National Transit Database, Federal Transit Administration

But perhaps the biggest if is the economic renaissance promised by MetroLink officials and proponents. Transit advocates claim that rail spurs economic development, that, once you put the rails in, the traffic generated by riders will induce all sorts of business growth. Unfortunately, this claim just doesn’t hold up. Many MetroLink stations are surrounded by land that’s either (a) already developed (and likely heavily subsidized), or (b) relatively empty. In fact, transit-oriented and adjacent development is so scarce in St. Louis that rail advocates have to cast an incredibly wide net for any evidence of it. For instance, Citizens for Modern Transit, the region’s major transit advocacy group, includes investments on Interstates 64 and 70 and parking garages as development “spurred” by MetroLink. And Metro, which operates MetroLink, seems to think any investment within a half-mile of a rail station is causally linked to the presence of their trains. (Or, all they present is data on development within a half-mile of their stations.) Perhaps this is why consultants are now saying that MetroLink could “spur possibly millions of dollars in economic development….” (my emphasis).

At this point, it’s unclear what, if anything, taxpayers will get in return for hiking up their sales taxes. Although rail proponents may have inexhaustible faith, history and facts suggest taxpayers won’t get much for their investment.