Taxpayer Largesse Unnecessary, Wasteful in U City Development

University City officials seem far too eager to give away taxpayer dollars to developers who are hardly in need of a handout.

Developers and officials in University City are pushing for a $70.5 million subsidy to help fund a $190-million development at Olive Blvd. and Interstate 170. The project is slated to include a Costco, apartments, restaurants and retail space. The taxpayer money would come via tax-increment financing (TIF), which captures increased sales, property and other taxes generated by a development to cover some of its costs. In this case, taxpayers would cover nearly 40 percent of the project’s costs!

The controversial project has raised a number of concerns. Some worry about gentrification, neighborhood and cultural disruption and the possible use of eminent domain to force out longstanding businesses. These topics are serious and ought to be debated at the June 22 public hearing on the potential development. But a fundamental problem with the project deserves more attention: the fact TIF is unnecessary and fails to deliver on its proponents’ promises.

First, TIF was intended to encourage development in areas where no one wants to invest money, which hardly describes the area under consideration. The developer’s proposal cites (see pp. 6–10) conditions such as cracked sidewalks, overgrown grass and overflowing dumpsters as evidence that the area is “blighted.” These conditions, though less than ideal, surely don’t make development so unappealing as to require $70.5 million in taxpayer assistance. The area surrounds a busy interstate interchange and is flanked by Olivette, Ladue, and Clayton—there’s a reason current businesses don’t want to leave!

More importantly, proponents are promising the public higher property values, increased tax revenue for city services, and a bustling, inclusive neighborhood should the subsidy be approved, but decades of research shows these promises are rarely kept. It was just in 2016 that the City of St. Louis released a mammoth report detailing the near-total failure of its incentive programs. From 2000 to 2014, St. Louis lost out on more than $700 million in revenue because of TIF and related programs for naught. “[W]hile there may be disagreement about the value of some [incentive] packages,” the report concluded, “it is clear that the City gains no net benefit from an extremely costly program with no real economic development impact” (p. 6).

The study also failed to find a significant connection between TIF and job creation or increased property values outside parcels directly benefiting from subsidies. “[T]here is little evidence of significance [sic] spillover effects around incentivized parcels after the use of incentives. Across most project types,” the report continues, “there is no significant change in the trajectory of assessed value, permit investments or jobs” (p. 5). Economists from across the country have found almost exactly the same thing. In short, there is little evidence to support claims that handing out taxpayer cash will usher in an urban renaissance in University City, or anywhere else for that matter.

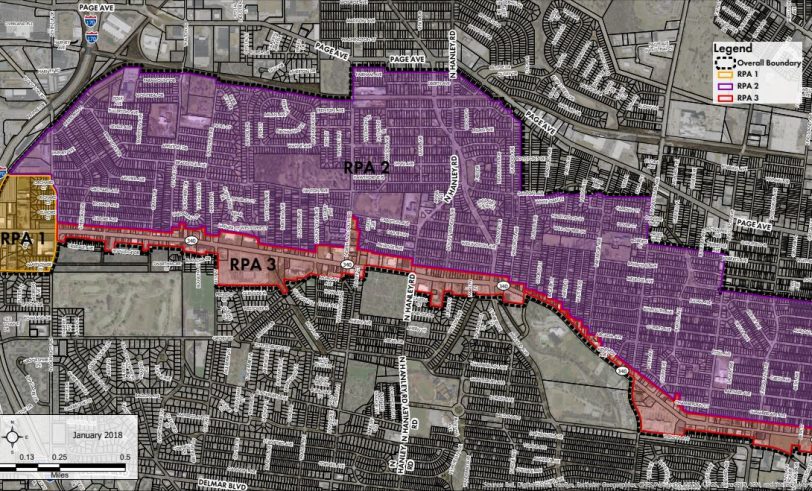

If officials and residents want to invest in University City’s third ward (where the proposed development would be located), there are other, more prudent ways to scratch cash together. Businesses and residents could form a community improvement district to collect property taxes—authorized by a public vote—to fund improvements. The “blight” designation assigned to the area as part of the TIF application would mean that those revenues could even be used to help fix up private residences. Before officials needlessly forego tens of millions in revenue over the next two decades, they owe it to University City residents to consider other options for improving the third ward.