The hit game Wordle is something I look forward to doing every day. While the prestigious and crowning achievement of completing it on my first guess still eludes me, I have learned how much the game is rooted in the science of reading. The English language is comprised of 44 word sounds (phonemes), and understanding how sounds and words are connected (phonics) can help you minimize your guesses. For example (no, I am not spoiling today’s puzzle), if the fourth letter of a five-letter word is “p,” this can help you eliminate some letters for the last spot without having to guess—such as “w,” “m,” and “j.”

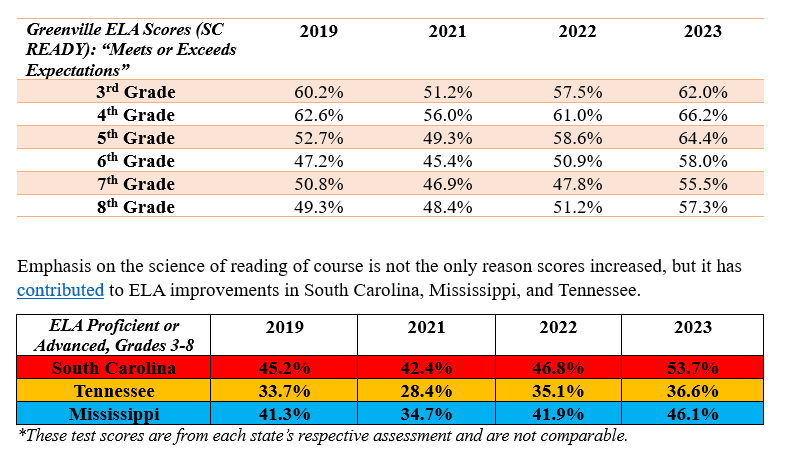

In a few states around the nation—particularly South Carolina, Tennessee, and Mississippi—dedication to the science of reading (explicit phonics instruction) has done more than solve Wordle puzzles. It has helped English/language arts (ELA) scores in these states surge past their pre-pandemic levels.

If you’re wondering if other states are experiencing a similar surge in scores, the answer is no. Researchers at Brown University have examined scores from nearly 30 states (data are not available for all states yet) and only Iowa, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee have exceeded pre-pandemic performances in reading.

With Missouri’s ELA scores continuing to decline post-pandemic (29% of Missouri 3rd graders had a below basic understanding of ELA), I believe that our new science of reading program, LETRS, will help our students, and I am happy that DESE is using it. However, I also think there is reason and opportunity to further commit to the science of reading.

For background, Missouri’s new LETRS program provides optional training opportunities for teachers in “evidence-based reading” and requires comprehensive reading examinations for K-3 students. Any student who is diagnosed or at risk for dyslexia must be provided evidence-based reading instruction. While this in itself is a good program, there is a key lesson from South Carolina, Tennessee, and Mississippi that we could adopt: Fully commit to the science of reading—for all students.

As I have discussed in previous posts, commitment to explicit phonics instruction could be key to making Missouri a leader in reading. Phonics instruction has a proven track record in independent research, in other states, and even in our own backyard. Back in 2019, the Greenville School District in South Carolina, with 77,000 students (largest in the state), failed to meet state literacy standards. Due to this, teachers in the district had to receive two years of training in the “science of reading” and use a new curriculum rooted in explicit phonics instruction. However, this “punishment” actually turned into a blessing: district scores on the SC READY state assessment have risen past pre-pandemic levels.

All three of these states have committed to the science of reading being the core of literacy instruction, while Missouri appears to emphasize it only after a struggling student is identified. When breaking out the scores by demographics, the data show that the science of reading was useful to all groups. While data were not available for Mississippi, ELA scores for every ethnic group improved at a near-equivalent rate in Tennessee and South Carolina.

In Tennessee, school districts with poverty levels between 0–10 percent and 15–25 percent saw the largest gains. In Mississippi, districts with poverty levels between 10–15 percent and more than 25 percent saw the largest gains. In South Carolina, districts with poverty levels between 15–25 percent saw the most improvement. These numbers demonstrate that students of all different backgrounds benefit from the science of reading, and it should not be compartmentalized into one particular group.

These states understand that our institutions of higher education are not adequately instructing our teachers how to teach reading. Mississippi requires that all prospective elementary school teachers pass a test in the foundations of reading (which largely includes phonics). Tennessee requires that all K-5 teachers complete at least one approved foundational literacy skills course. South Carolina requires classroom teachers to use evidence-based reading instruction that includes phonics. These states have also tied the science of reading to their third-grade retention strategy, which may be valuable for Missouri to evaluate. Missouri should strengthen LETRS by creating a requirement for all elementary teachers to participate in the program, and further commit by targeting science of reading instruction to all students, not just the ones struggling.