First the Fed pause, now the unpause: what do recent data and events mean for the U.S. economy? Just last week, the Federal Reserve announced that it was restarting its campaign of interest-rate hikes to curb still-too-high inflation. What is yet-to-be-determined is whether the most recent hike—which took the target federal funds rate to 5.25% to 5.5%—is merely an encore or a sign of future hikes to come.

This same ambiguous outlook applies to the U.S. economy as a whole. On the one hand, data released by the Department of Commerce last week reveals that real gross domestic product (GDP)—the value of all goods and services produced by the US economy, adjusted for inflation—increased at a 2.4% pace in the second quarter, following 2% growth in the first quarter. If this pace continues—a big if—then the economy will have safely avoided recession territory, having rebounded modestly from the two quarters of negative GDP growth at the beginning of 2022.

But past is not prologue. The economy still faces multiple headwinds that leave the risk of recession—or at least a significant weakening of growth—very much on the table. For one thing, the effects of monetary policy (i.e., rate hikes) on the economy operate with a time lag. The primary mechanism through which rate hikes fight inflation is by making borrowing costlier, thereby discouraging the demand for spending and, with it, the pressure on prices. The medicine from earlier doses of rate hikes is already having an effect on the economy; headline CPI inflation fell to 3% year-over-year last month, down from a peak of over 9%. However, rate hikes from late spring have not yet fully reverberated throughout the U.S. economy. Even so, the recent GDP data indicate that consumer spending only grew by 1.6% in the second quarter, with durable goods spending only growing by 0.4%. This particular subset of spending is useful as a gauge because durable goods like washing machines and other expensive household items are often purchased using credit, which now commands higher interest rates because of the Fed’s actions.

Another headwind facing the economy is the impending resumption of student loan repayments this fall. Make no mistake: student loan repayments ought to resume. Bailing out student debt by transferring it from the people who are reaping the financial gains from their education to taxpayers is regressive, fiscally irresponsible, and inflationary. However, this reality does not take away from the fact that people will feel the sting of being required to pay debts that they have been shielded from during the past few years. Consequently, consumer spending growth is likely to slow further or even turn negative. Considering that consumer spending contributed 1%age point (out of the 2.4) to GDP growth in the second quarter, a hypothetical scenario where consumer spending growth flatlines would by itself reduce GDP growth to just 1.4%. Moreover, another important component of GDP—investment—is sensitive both to rates themselves as well as business expectations about future consumer demand. It is entirely plausible—maybe even likely—that investment growth will decline from its most recent rate of 5.7%, and if that happens, GDP growth could easily fall below 1%.

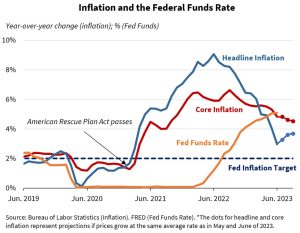

Still another important headwind is the fact that, for all the progress the Fed—and the Fed alone—has made in combatting inflation, it has not yet succeeded in achieving its 2% target. As shown in the figure below, headline inflation is down to 3%, but core inflation—a better measure of fundamental pricing pressures—is still nearly 5%. Moreover, because the inflation readings are year-over-year measures, and because the monthly numbers from July and August 2022 were very low, it is quite possible that the headline year-over-year inflation numbers may rise modestly over the next few months.

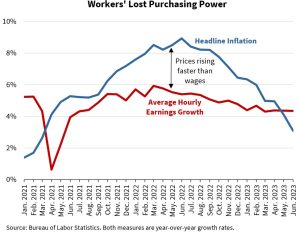

Lastly, and arguably most importantly, the U.S. economy has been facing a productivity crisis over the past two years. Productivity—that is, economic output per hour of labor—has decreased by nearly 2.5% since the second quarter of 2021, which is unprecedented. By comparison, productivity rose by nearly 5% from the first quarter of 2017 to the fourth quarter of 2019. Not coincidentally, that earlier period corresponded with household income rising by over $5,000 after inflation—meaning higher purchasing power—as compared with the recent decline in purchasing power of over $2,000. The figure below gives a stark visual reminder that prices have grown consistently faster than wages since the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act “stimulus” bill in early 2021, with price growth decreasing only in response to the Federal Reserve’s interest-rate-hiking campaign.

As speculation continues over the near-term trajectory of the U.S. economy, it is worth mentioning again the essential need to raise productivity—not just to avoid recession, but to lift the economy out of the doldrums of 1% to 2% growth and return to or exceed its historical norm of 3% growth. While these numbers may seem difficult to relate to, a rule-of-thumb may prove useful. The amount of time (in years) that it takes for the U.S. economy to double in size is roughly 70 divided by the growth rate. Thus, if an economy grows at 3% per year, it will take approximately 70/3 = 23.3 years to double in size. By contrast, if the economy grows at 2% per year, it will take 70/2 = 35 years to double, and it will take 70/1 = 70 years to double if growth is persistently only 1%. That would be a disaster for the U.S.’s potential to remain the leading economy in the world.

So how do we achieve growth liftoff? Answering this question is much too large for a single blog post, but the key is productivity, and one important point to remember is that raising productivity is not about squeezing more out of workers and making life at work more of an unpleasant grind. Quite to the contrary. The most effective way to increase productivity is to ensure that workers are equipped with the skills to succeed, unencumbered by regulations to find the best occupation and employer to realize their potential, and where both workers and employers are able to keep more of the fruits of their productive activity. That phrase—productive activity—is key to keep in mind. While public debate often focuses on spending, spending, spending, it’s time to shift our attention to producing.