Debt Ceiling Deal Q&A

After a whirlwind period of tense negotiations, the House of Representatives and White House agreed this week on raising the debt ceiling and pairing it with reforms to spending, work requirements, and permitting. The Senate passed the bill and sent it to the President’s desk today. As is commonly the case with bills passed under a divided government, nobody is completely satisfied, and there is considerable confusion about what the deal actually does as well as what it means for the average person. Following are answers to some of the most common questions about the deal.

What is the debt ceiling, and what would have happened had we not raised it?

The debt ceiling (or debt limit) is a legal limit on how much money the U.S. government is authorized to borrow. Once the country reaches this limit, the Treasury is not permitted to issue more debt.

Can we simply not raise the debt limit?

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the federal government will run a deficit of more than $1.5 trillion in 2023 alone, with spending amounting to $6.4 trillion and revenue coming in at $4.8 trillion. Of the $6.4 trillion in spending, $4 trillion is for mandatory programs that operate without Congress needing to regularly reauthorize them (e.g., Social Security and Medicare), $1.7 trillion is discretionary spending, and $660 billion goes to interest payments. Balancing the budget and eliminating the deficit in one fell swoop would require essentially zeroing out discretionary spending or making instant, draconian cuts to mandatory programs. Given the deep fiscal hole that the federal government has put the country in, there was no real alternative to raising the debt ceiling.

If both sides agreed that the debt ceiling had to be raised, what were the negotiations about?

Historically, occasions when the government has reached the debt ceiling have produced negotiated agreements that both raise the ceiling and limit spending, as was the case with the Budget Control Act of 2011 during the Obama-Biden Administration. However, this time around, the White House insisted for months that it would not negotiate on any spending reforms as part of raising the debt ceiling.

Given the unsustainable fiscal path that the United States is on, the White House was essentially sending the message that the only way to avert a debt crisis now (by raising the debt ceiling) was to cement the current spending trajectory in place—and thereby increase the chance of a debt crisis down the road. The House of Representatives disagreed with this false choice between a debt crisis today and a debt crisis later and instead passed the Limit, Save, and Grow Act, which simultaneously raised the debt ceiling and slowed the trajectory of spending, among other reforms. Passage of this bill forced the White House to the table, abandoning its no-negotiations stance on spending reforms.

What is contained in the debt ceiling deal?

The debt ceiling deal contains a number of elements. First, it raises the debt ceiling through the end of 2024 and it establishes spending caps for fiscal years 2024 and 2025 that limit the growth of spending to 1% with tough enforcement provisions during the appropriations process, which is when Congress formally makes detailed, program-level spending decisions. In addition, the bill prescribes a 1% cap on spending growth through 2029. By way of comparison, the CBO projected an 8.1% jump in discretionary spending between 2024 and 2025, followed by average annual increases of 2.8% through 2033.

Besides affecting topline spending, the debt ceiling bill rescinds certain COVID-19 and IRS funds, expands work requirements for food stamps and welfare, and implements energy-permitting reforms to reduce delays from excessive and unresponsive bureaucracy.

What is the overall effect?

The CBO projects $1.5 trillion lower spending growth (or in Washington, DC parlance: cuts) because of the deal. Without the deal, discretionary spending would have risen from $1.7 trillion in 2023 to $2.4 trillion in 2033, whereas now the projection is for $2.2 trillion in discretionary spending in 2033.

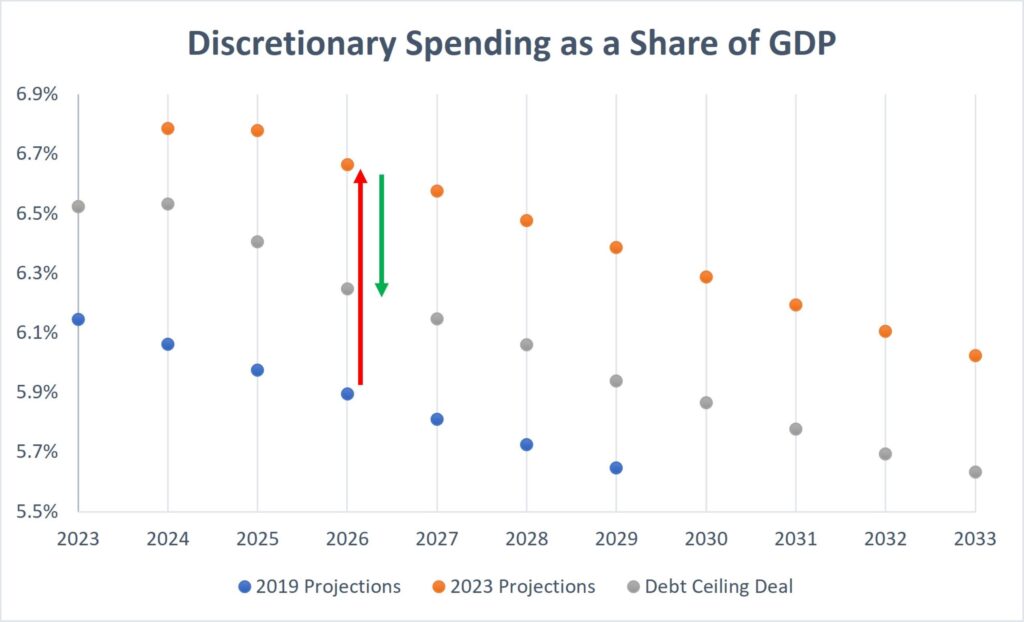

To give further perspective, the figure below plots three different projections for the path of discretionary spending as a percentage of the country’s annual economic output. The blue dots are CBO projections made in fall 2019 under the previous administration and before COVID-19. The orange dots are CBO projections from this May, but before the debt ceiling deal. The red arrow showing the upward shift from the blue dots to the orange dots represents the persistent increase in discretionary spending under the current administration’s policy plans. The gray set of dots represent discretionary spending under the debt ceiling deal, with the green arrow showing the reduction relative to what was slated to occur before the deal.

As the figure makes clear, the debt ceiling deal essentially takes discretionary spending halfway back to the path it was set to follow before COVID-19 and the change in administration.

Figure 1: Discretionary spending as a percentage of GDP. Source: Congressional Budget Office, Show-Me Institute calculations.

Figure 1: Discretionary spending as a percentage of GDP. Source: Congressional Budget Office, Show-Me Institute calculations.

How should Missourians view this deal?

The United States faces a profound and troubling fiscal situation with its unsustainable spending levels, not to mention slow economic growth, declining productivity, and inflation that remains much too high. It is important to recognize that the country has a spending problem, not a revenue problem. Federal revenues are currently above historical average, but the reason deficits are so large is that spending as a share of GDP is higher than it has ever been over the past century except during peak COVID-19 and World War II. The debt ceiling bill does not fully reverse the spending increases of the past two years, but it represents a step in the right direction, especially compared to the White House’s previous no-negotiations spending stance.

Taking a step back, whereas the debt ceiling debate focused on discretionary spending, the vast majority of federal spending goes to mandatory programs, chiefly entitlements. The CBO projects that, absent reforms, federal spending will rise from 23.7% of GDP in 2023 to over 30% by 2053, annual deficits will more than double to over 11% of GDP, and the national debt will balloon to almost 200% of GDP. In this scenario, interest payments on the debt would triple as a share of the economy and would represent the single largest spending item for the U.S. government. Even this scenario is rosy in that it assumes an infinite willingness among investors to buy U.S. debt regardless of how dire the fiscal picture becomes—a rather implausible assumption that America would be wise not to test.

Going forward, much work remains to be done to right-size government and revitalize economic growth so that Americans can enjoy a more prosperous future free from the risk of steep tax hikes, crippling inflation, debt crises, and adversarial foreign governments buying up large quantities of government debt. The debt ceiling deal is by no means a cure to the country’s current fiscal ills, but it’s one step in the right direction, and the starting point for a much-needed national conversation.