Missouri’s low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC) is a classic example of throwing good money after bad. The program—which provides $1-for-$1 in matching funds to supplement the federal LIHTC created in 1986—awards credits to developers to offset construction costs in exchange for agreeing to reserve a fraction of units for low-income tenants.

Despite having some of the most affordable housing costs in the country, historically Missouri spent the second most of any state on LIHTC, which is consistent with research finding that the LIHTC program is poorly targeted. What’s worse, multiple state audits in Missouri have found that less than $0.42 cents of each dollar are spent on actual construction. It wasn’t until 2017 that Missouri finally faced up to the failures of its LIHTC program and suspended it. But no longer.

After a three-year shutdown, Missouri is now reviving its LIHTC program with grand promises of reform. Specifically, the Missouri Housing Development Commission (MHDC) stated that it will cap the state’s yearly LIHTC awards at 70 percent of the annual federal allotment, and the legislature is considering enshrining the cap into law. The benefit of the cap is that instead of state taxpayers being on the hook for $180 million per year, they might only be out $135 million. However, a smaller loss is still a loss, and good stewardship of taxpayer funds means insisting that programs deliver value and achieve results.

Given the structure of the LIHTC program, even the aforementioned savings are likely to take years to materialize, if ever, assuming that legislators don’t backtrack on reforms. In particular, the LIHTC awards credits not all at once but rather in equal allotments over ten years. As a result, the savings from any reduction in credits will also take a decade to gradually phase-in.

The tendency of the federal allotment to rise each year and the creation of a new MHDC pilot program that increases the payout rate for some state projects both may lead to further backloading of savings. Specifically, the pilot program will allow 20 percent of projects awarded credits to redeem the awards on an accelerated schedule that matches the federal yearly allotment at the full 100 percent in the first five years before evenly spreading out the remaining funds over the final five years.

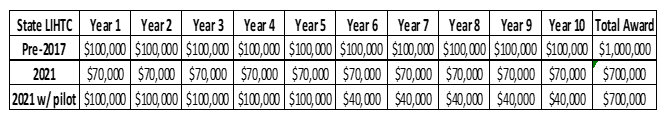

The table below gives a concrete illustration. Before 2017, a project that was eligible for $1 million in federal credits would also have been eligible for $1 million in state credits with awards distributed over ten years. Under the new cap, the total state credit falls to $700,000, which amounts to $70,000 each year. However, under the pilot, the project could receive $500,000 of the $700,000 in just the first five years—matching the $100,000 per year that it would have received before 2017—and then claim the final $200,000 in the last five years. In short, taxpayers would not see any savings from the cap until after five years, which gives vested interests more time to reverse reforms before they ever take hold. Though the idea behind the pilot program may have some merit, the bottom line for taxpayers is still delayed and potentially uncertain savings.

Spending less on an inefficient LIHTC program is better than spending more, but it will do taxpayers a disservice if lawmakers use this superficial change as an excuse to declare success, move on, and not undertake more fundamental reforms.