John Sherman, the owner of the Kansas City Royals, said in an announcement the other day:

I believe in my gut that the timing is right for the Royals to become residents of the Crossroads and neighbors to Power & Light, 18th & Vine and Hospital Hill, helping to further connect the cultural center for our great city.

What’s important to note is that Sherman plans to include an entertainment district in the construction. Mike Hendricks of The Kansas City Star adds: “The imagined $1 billion-plus ballpark would be bordered on the east by office, retail and residential development, which would be a potential source of revenue for the team.”

No one should doubt that this publicly funded stadium with all the additional accouterments would be good for John Sherman. But will it be good for his neighbors?

Remember that all sorts of research and many economists make it clear that sports stadiums “are really poor public investments.” Part of the reason that the economic impact studies released by proponents of such efforts are flawed is that they count only the new spending at the new location—not the reduction of spending elsewhere. In a 2017 report, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis concluded: “economists generally oppose such subsidies. They often stress that estimations of the economic impact of sports stadiums are exaggerated because they fail to recognize opportunity costs.”

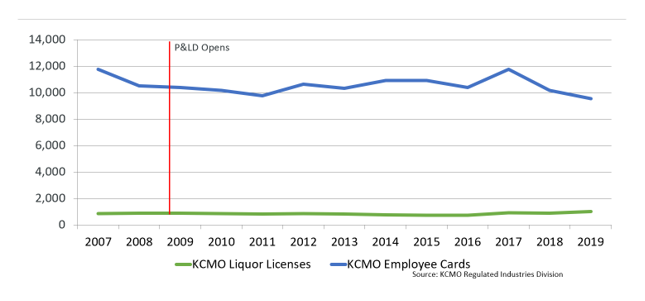

Consider the Power & Light District. According to the Regulated Industries Division of Kansas City, Missouri, the number of liquor licenses (a gauge of how many restaurants and bars are operating) and employee health cards (a proxy for the number of people employed at bars and in food service) remained flat citywide for a decade after subsidies were awarded.

The Power & Light District didn’t create new jobs or businesses. It merely moved them from elsewhere in the city to downtown. And it moved them from places where the city, county, and school districts were collecting property, sales, and income tax revenue to a place where those taxes are diverted back to the developer to offset the cost of construction.

Even if you consider the Power & Light District on its own merits, it has failed to be successful. Thomas Friestad reported last year in the Kansas City Business Journal that Kansas City has had to meet multimillion-dollar debt-service obligations because the district does not generate enough revenue to pay its own debts. Those payments have ranged from $6 million to $17 million, amounting to over $160 million since 2006.

Just as with the Power & Light District, John Sherman’s entertainment district will not create new economic activity. It will only move it from elsewhere in the city. On game day, fans who now stop at grocery and liquor stores on their way to tailgate may instead go to bars at the stadium. That is not new activity—just different activity. Fans who might have gone to Power & Light, or to other places in the Crossroads District, may now go to the bars that Sherman owns. That is not new spending—just different spending. This is exactly what happened when Ballpark Village opened in St. Louis; it cannibalized other existing businesses.

The economic impact studies that will inevitably be produced to tout this new entertainment district will likely only count the new spending in the new location—not the loss of spending elsewhere.

To the degree that the Royals’ new entertainment district leeches spending away from Power & Light—which seems like it may be the intent of Sherman’s gambit—Kansas City taxpayers will face even higher annual debt obligations than now.

A publicly funded downtown stadium and entertainment district will be good for John Sherman. It won’t be good for anyone else.