In a debate about the efficacy of pre-K, Kansas City Mayor Sly James was dismissive of research that suggested there might better ways to help low-income children achieve better education results. We’ve heard others tell us they don’t care about policy research, which is at best an unreasonable and potentially dangerous view, especially coming from a public official.

On Tuesday, March 12, I appeared as a panelist on an American Public Square discussion titled “Pre-K for All?“ about the upcoming April ballot measure. Proponents of pre-K point to a single, small-scale study of a specific pre-K program conducted from 1962 to 1967. The study, called HighScope Perry, did show a positive relationship between participation in the program and educational and financial success. However, the program that was studied was intensive, expensive, and only included 123 children. While the Mayor and Mid America Regional Council (MARC) specifically cites the HighScope Perry study, the plan they endorse for Kansas City is nothing like what was done there.

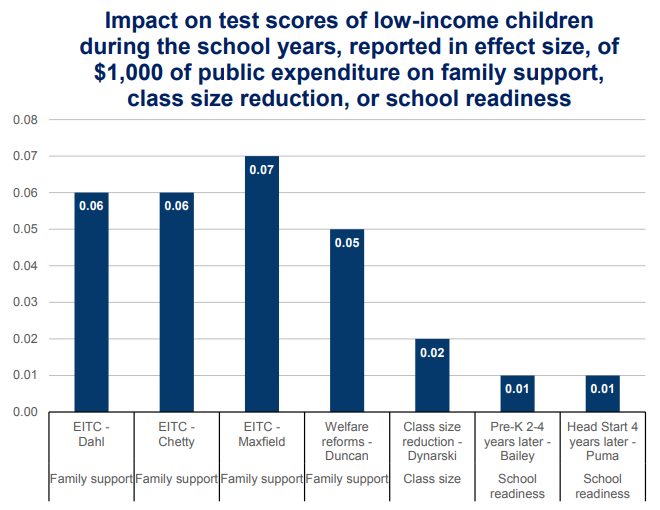

Russ Whitehurst of the Brookings Institution has written at length about the failure of larger-scale pre-K programs such as Head Start and the Tennessee Voluntary Pre-K Program to generate impressive results. We’ll discuss that research more in future blog posts. But in a survey of the research on various school-readiness interventions, Whitehurst pointed out that direct aid to families, such as the earned income tax credit (EITC), “produced substantially larger gains in children’s school achievement per dollar of expenditure than a year of preschool, participation in Head Start, or class size reduction in the early grades.” That is a fascinating bit of information and should be of interest to anyone who is serious about helping low-income children.

During the panel discussion I offered, “You could do more for poor families in Kansas City by removing the sales tax on food and by exempting, say, the first $26,000 of earnings from the earnings tax. You can do more by aiding families—giving them more money in their pocket—than you can by taxing them and providing a program.”

But Mayor James was not having it. He responded, “There’s no way that you can tell me, regardless of what study you may cite,” that by reducing taxes on the poor that they, “are going to use the money to educate their children.” And maybe they won’t, but the data Whitehurst cites don’t specify how families spend the extra money. EITC funds are not earmarked, yet this direct support to low-income families still outperformed pre-K according to Whitehurst’s research.

Perhaps what low-income families need is not to have more money taken away from them in order to provide them more services. Perhaps what they need is more money, more flexibility, more agency to address their own challenges as they see fit. Perhaps telling poor people that government knows best how to spend their money and educate their children isn’t the best way to solve problems. The research (at least if we go beyond a specific study that seems cherry-picked to support a rosy view of Pre-K programs) seems to suggest this, if only policymakers will listen.