Suppose your boss comes to you one day and asks you to take a survey. He or she asks you, “When considering the components of compensation, please indicate the level of priority you feel that management should give to each. Your choices are more pay (an increase in base salary), performance pay for certain metrics, better health care benefits, or other stipends such as loan forgiveness or housing allowances. What do you choose?”

If you are like most people, you’d choose more pay.

If this survey were conducted with everyone in your company, what would it tell you?

It would tell you compensation preferences among people currently employed by the company.

That’s it.

It would not tell you whether boosting compensation in these ways would increase retention. It wouldn’t tell you whether you’d get more candidates applying for jobs if you did these things.

Of course, you may infer those things . . . but you could be wrong.

If you wanted to know those things, you’d need to design a better survey and you may need to survey different people.

For instance, if you want to know why people are leaving or staying, then you should ask that question. You should ask people who left the job why they left and what would have enticed them to stay. You should ask current employees if they’ve thought about leaving the company and, if so, why? Those questions would help you better understand how to retain people within your company.

Similarly, if you want to know more about recruiting applicants, you’d need to ask different questions and ask questions of different people. You’d ask your employees, “What attracted you to this job?” You’d ask people not employed at your company if they ever thought about applying for a job at your company and what would entice them to work for your company.

The questions you ask matter, and poorly designed surveys do little to help us answer the questions we really want answered.

Now imagine you were going to base a $29.5 million decision on the results of this survey. You’d think you’d want to get the questions right.

Well, you would unless you were the state’s Blue Ribbon Commission looking at the state’s teacher shortage.

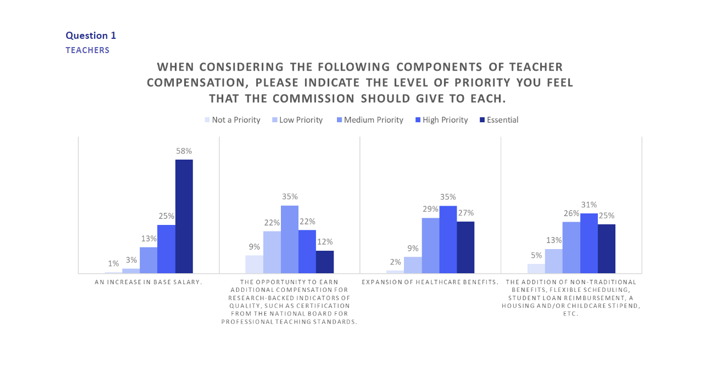

The figure below shows the question the commission asked teachers. As Gomer Pyle might say, “Surprise, surprise, surprise.” Teachers want what anyone asked this question might want—more money!

I’m not saying we shouldn’t pay teachers more money. Maybe we should. What I’m saying is that that the state should not base important and complex decisions on poorly constructed surveys that tell us what we should already know—people like being paid more.