In Missouri, a single parent employed full time at a minimum wage job will still be in poverty. Some see this as justification for raising the minimum wage, on the grounds that no one who works full-time should be in poverty. This argument has been part of the drive to raise the minimum wage, and that campaign has led to a minimum wage increase proposal on the statewide ballot for November.

While the situation for single parents working minimum wage jobs is undoubtedly difficult, increasing the minimum wage can harm people in that position, as well as those struggling to hold down a job. After Seattle increased its minimum wage, low-wage workers had their hours cut, and the number of minimum wage jobs decreased. In fact, it is the people without steady employment who are much more likely to be in poverty and who are hurt the most by the unintended consequences of a higher minimum wage.

In a working paper for the American Enterprise Institute, Angela Rachidi uses data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to show that most families who have one adult consistently working are not in poverty—and if they are in poverty, it is likely to be for short periods of time. SIPP data give us unique insights because they follow the same families for 36 months and track their poverty and job status during that time. When measuring the federal poverty rate, on the other hand, the Census Bureau merely asks families if they have been in poverty at all in the past 12 months but nothing else about their situation.

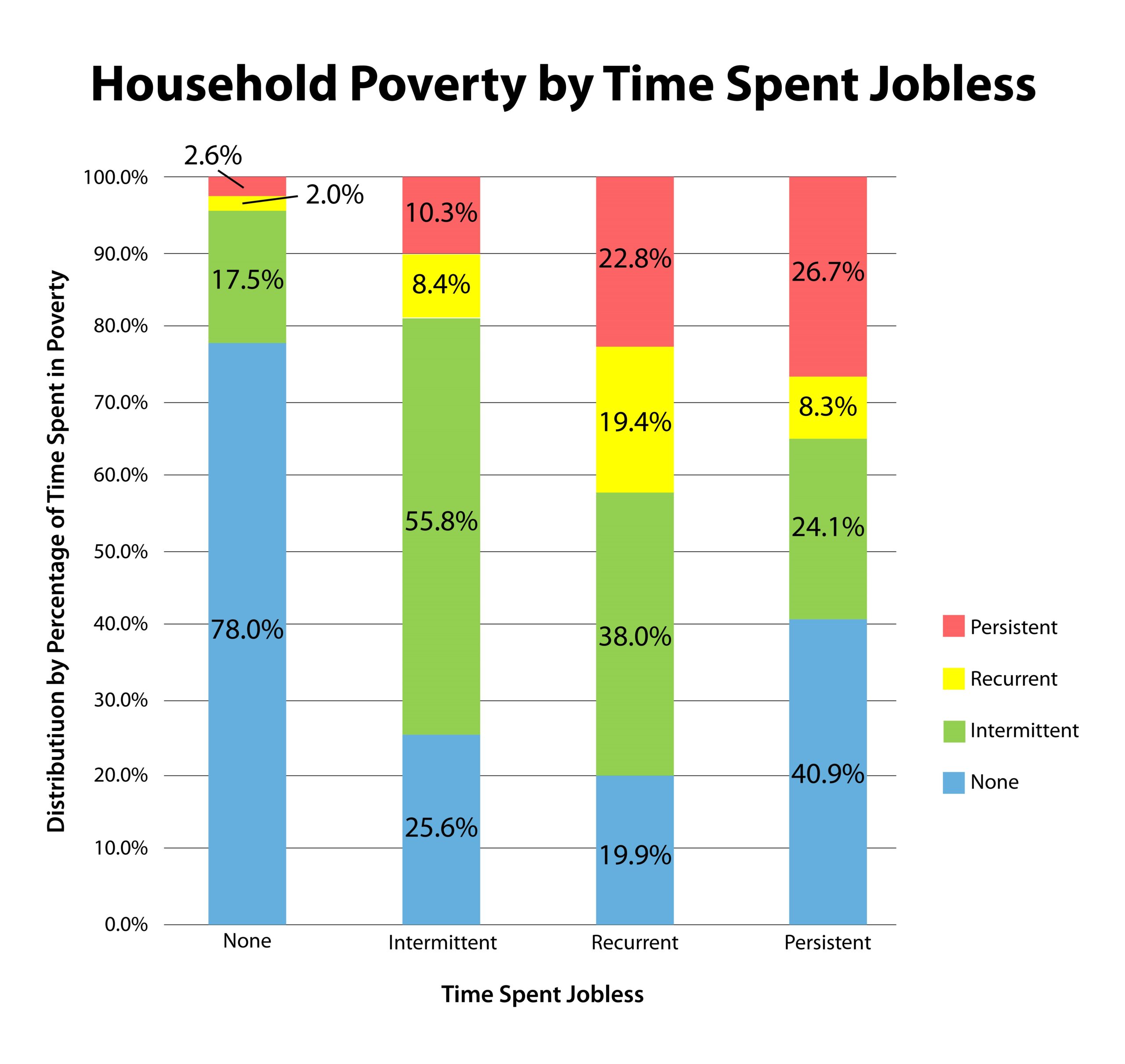

One chart (below) from the paper sheds light on the economic situation of American families and how often they were in poverty or unemployed. The far-left bar represents families where at least one person held a job for the entire 36-month survey period. In this group, 78 percent were not poor at any time, 17.5 percent were poor for 1 to 18 months, 2 percent were poor for 19 to 27 months, and 2.6 percent were poor more than 27 out of the 36 months they were surveyed.

Intermittent = 1 to 18 months of the three-year period. Recurrent = 19 to 27 months of the three-year period. Persistent = more than 27 months of the three-year period.

Source: Rachidi, Angela; American Enterprise Institute. Persistence of Poverty and Joblessness in US Households. AEI Economics Working Paper. July 2018. Figure 5 (Author’s calculations using the Survey of Income and Program Participation, 2008 Panel, Years 2009–11, Waves 2–11).

Those who experienced intermittent and recurrent joblessness (two middle bars) were much more likely to be in poverty at some point during the survey period. These people are having difficulty getting hired at the current minimum wage. For those who are persistently jobless and do not have income from retirement or disability insurance to keep them out of poverty, the barriers to entering the job market are also high. Mandating that employers pay even more for their labor will only take away employment opportunities and make it even harder for them to get a foot in the door toward more stable employment.

A better solution would to be implement an earned income tax credit (EITC) here in Missouri so that those who are working can hold on to more of their paycheck. Instead of making low-wage workers pay a state income tax, a non-refundable EITC could reduce or even zero-out their state income tax bill and increase their take-home pay.

It’s understandable to want to do something for people who work hard but still can’t escape poverty. But just because a policy is intended to fix a problem doesn’t mean that it will actually work. Missourians risk creating a worse system with a higher minimum wage that benefits the few who consistently work while harming many more who face low earnings due to frequent unemployment or underemployment.