Like a Sore Thumb: Missouri’s Testing Standards Buck National Trend

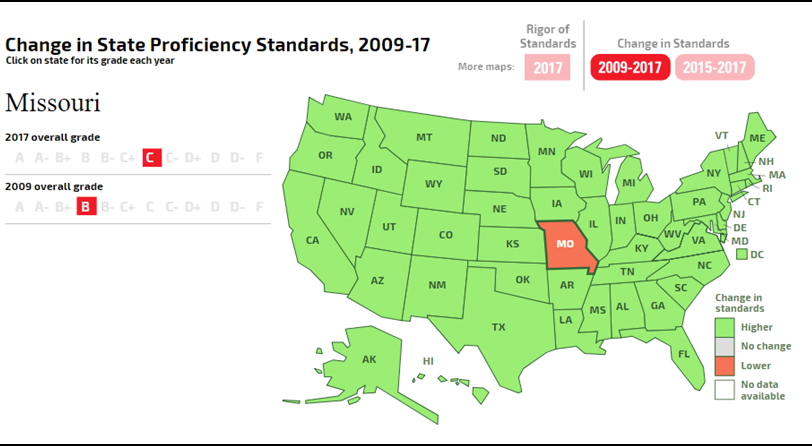

Marching to the beat of your own drummer is all good and well as long as you know where you’re going. A recent study published in Education Next suggests that Missouri—alone out of all 50 states—is headed in the wrong direction with regard to state proficiency standards for students. The study compares how well students in each state do on their states’ proficiency tests to how well they do on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). For example, if 25 percent of students in a state scored proficient on the state’s test, but 50 percent scored proficient on the NAEP, that would indicate that state’s proficiency standards are more rigorous than the national standards. Since states have different state assessments and the NAEP is administered in every state, the NAEP serves as a Rosetta stone and allows us to compare the standards of different states. According to the analysis, every state in the nation increased the rigor of their proficiency standards from 2009 to 2017. . . except Missouri. This could have significant implications for Missouri students, especially students in Missouri’s most disadvantaged school districts.

When a school district in Missouri loses accreditation, students are allowed to transfer to a higher-performing school district. In recent years, thousands of students from the Normandy and Riverview Gardens School Districts used this provision in state statute to transfer to some of the highest-performing school districts in the state. But students lost the right to transfer when the state board of education voted to give the school districts provisional accreditation, based in part on improvements in student achievement-test scores. Based on the Education Next study, we have to wonder whether those learning gains were just an illusion caused by the state making the test easier.

It is important to understand this analysis is not comparing the rigor of the learning standards in each state. Standards say what students should learn in each grade. The relevant measure here is what students must score to be considered proficient by the state assessment. While the tests are developed based on the standards, setting the cut-score is a subjective process. The lower the cut-score, the higher the percentage of students who will score proficient.

In 2009, Missouri had among the most rigorous assessments in the nation. The two images below come from a report from the U.S. Department of Education, “Mapping State Proficiency Standards Onto the NAEP Scales.” Look far to the right and you will notice that Missouri led the nation in rigor on the 8th grade reading assessment and had the third most rigorous state assessment in 8th grade mathematics.

What followed 2009 was chaos. Missouri adopted the Common Core standards and ditched our rigorous state assessment. The state then went through turmoil as citizens pushed back against the Common Core, the legislature called for new standards to be written, and the state shuffled through four different state assessment systems. In the end, we wound up with an assessment that was easier than the one we had before.

Forget for a moment the overall message that lowering standards sends and the potential it has to impact all students. In the cases of Normandy and Riverview Gardens, lowering standards may have had a direct and detrimental impact on students. The year Normandy lost its accreditation, just 22 percent of the district’s students scored proficient or advanced in communication arts and 23 percent did so in math, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. In 2017, the district regained provisional accreditation even though the performance of students in the district was not substantially better. That year, 34 percent of students scored proficient or advanced in communication arts and only 19 percent did so in math. Keep in mind these scores were with the easier tests.

Missouri’s state board of education voted to give provisional accreditation to the Riverview Gardens School District in 2016 and the Normandy Schools Collaborative in 2017. It seems those decisions may have been based on the faulty assumption that the student achievement in the districts was improving, when it seems the state was just giving easier tests. At the very least, we owe it to the students of these districts to investigate this further.