In 1988, kids enjoyed their video games on an 8-bit Nintendo, people listened to music on cassettes, and the World Wide Web did not yet exist. Things have changed a lot in the past 30 years. Indeed, the rapid development of technology has improved almost every aspect of our lives. Yet, something strange has happened in Missouri when it comes to educational assessment. Despite three decades of unprecedented growth in technology and our understanding of testing, the standardized tests we administer today are worse than they were in 1988. That’s right. After 30 years and millions of dollars in research and development (maybe billions if you include what has been spent nationwide), our tests tell us less than they used to.

Missouri’s first statewide movement toward test-based accountability came in 1985, when lawmakers passed the Excellence in Education Act. Yet in 1988, Missouri still did not have standards or testing as we know them today. Instead, schools used the California Achievement Test, a standardized testing package sold by the McGraw-Hill publishing company. It is a norm-referenced aptitude test.

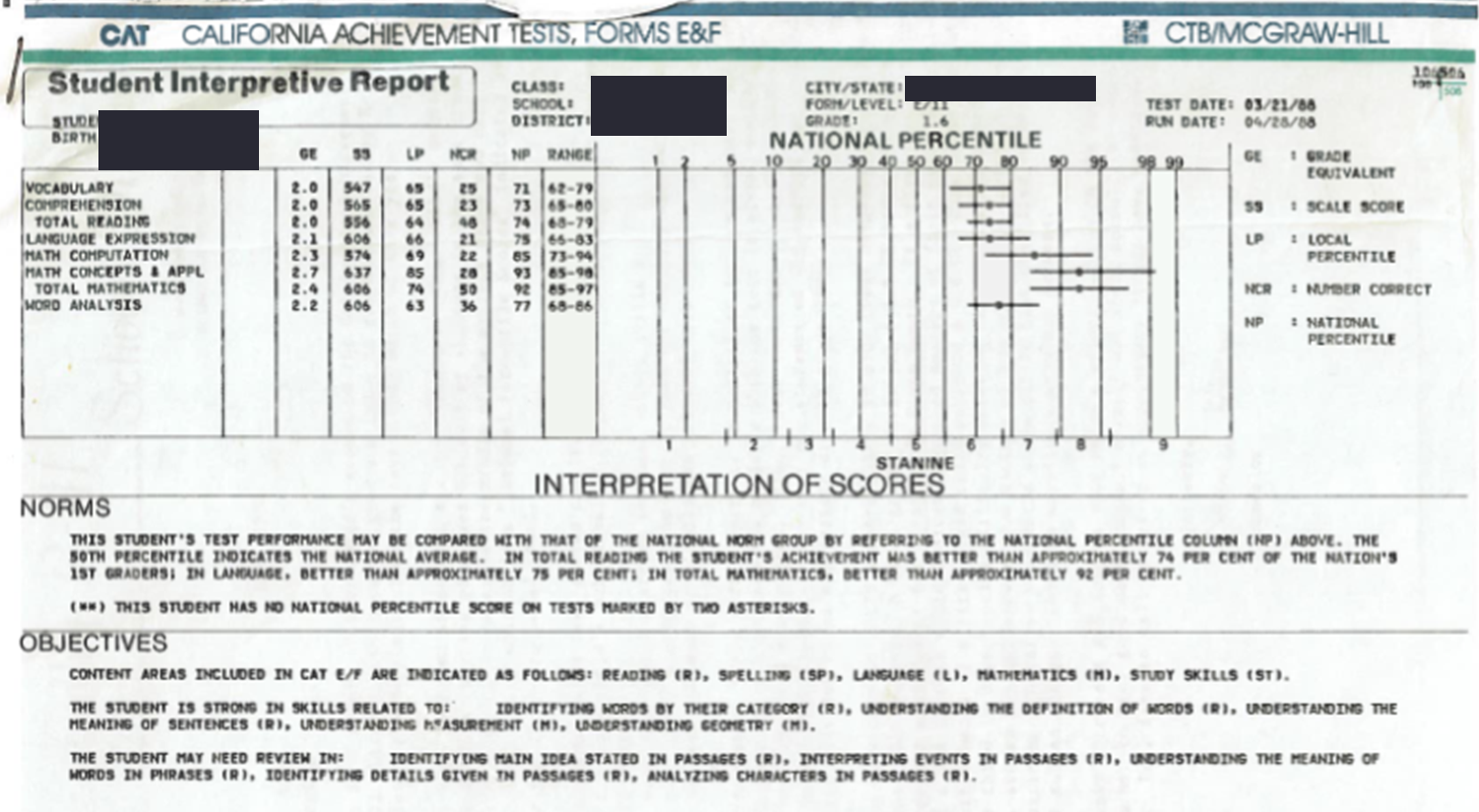

After students took the test, a report like the one below would be sent home. It told parents a lot about how their child performed. Parents could see their child’s Grade Level Equivalent, which indicated whether students were on track. They could also see how their child stacked up to other kids locally and around the nation with percentile ranks. Moreover, the report indicated specific strengths and weaknesses for each student. In other words, the tests actually told you something. Unfortunately, that’s not the case today.

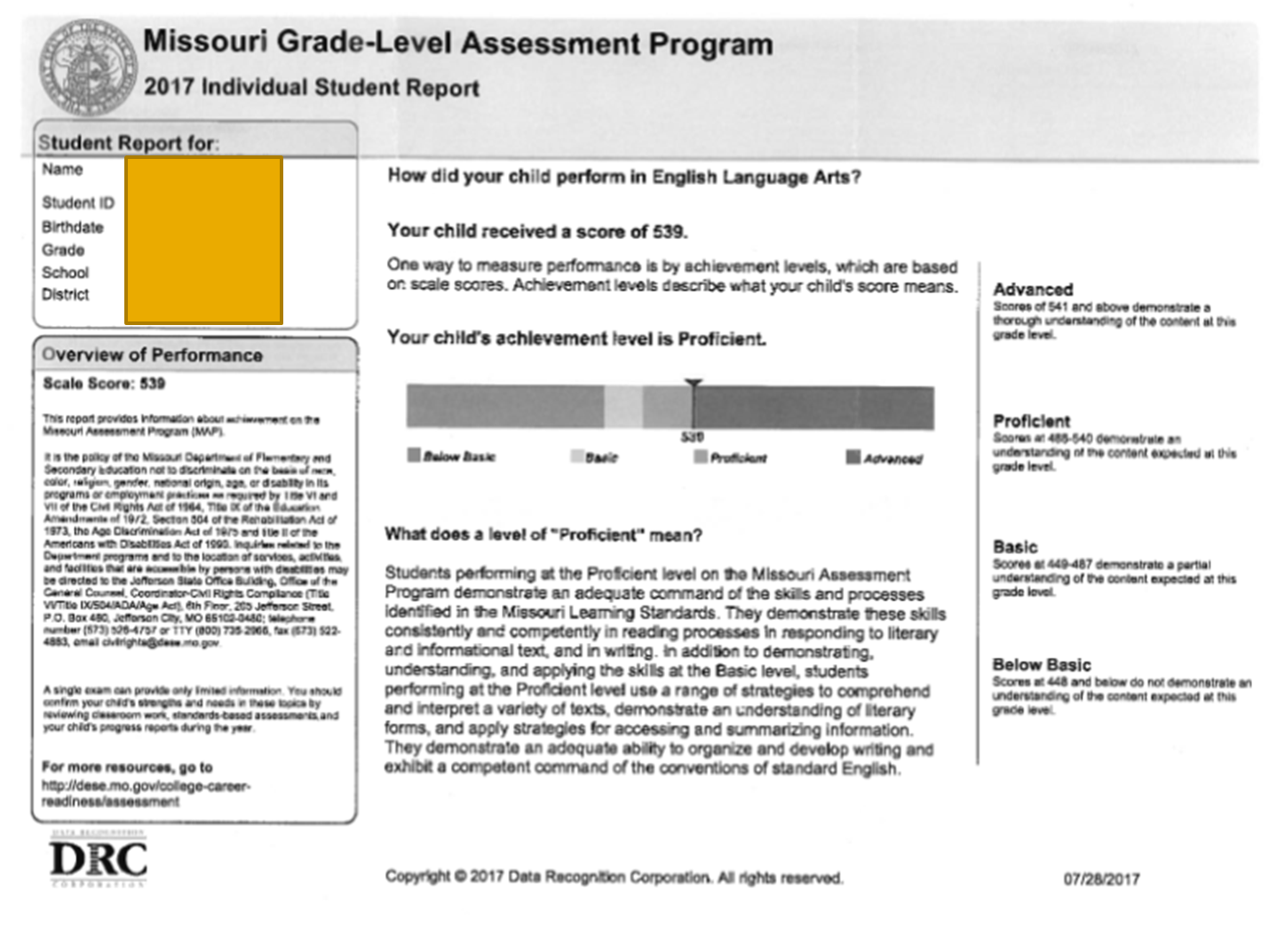

Fast forward to today. Missouri has developed standards for each grade, and students are tested every year in grades 3 through 8 and in various high school subjects. The state has spent considerable time and resources to develop a comprehensive accountability system built on standardized tests. Take a look at the report below and see what we have accomplished in the past three decades.

This report from a year ago gives parents little to no useful information. In fact, there are only two important pieces of information on the entire page: the scale score and the level of proficiency. The former is useless, and the latter is inadequate. The scale score, as presented here, has no meaning. What is a 539? What’s the lowest score possible? What’s the highest, the average, etc.? We can make no sense of 539 because we are given no context. We can see whether our children are “below basic,” “basic,” “proficient,” or “advanced,” but even this doesn’t help us much because we are not told any specific information about our child. Take a look at the section that explains what “proficient” means. If offers broad generalizations, whereas the 1988 exam offered student-specific suggestions.

Keep in mind, parents still have to wait roughly four months to receive these results. Even if the results weren’t useless, they’d almost be obsolete by the time they arrived.

How is it possible that we have come so far and not gotten anywhere?

It’s time for a change, and Missouri school leaders know it. St. Louis Public Radio has reported that more than 40 superintendents have formed the Missouri Assessment Partnership in an effort to improve these tests. They want to do so because the tests are used for school accountability, but we also need changes to make these tests provide useful information to parents.

Standardized testing can serve a useful purpose, but not if we can’t make any sense of the results.