I’ve been giving a lot of thought lately to the findings of Missouri’s blue ribbon commission. In my last post, I lamented the fact that the commission used a very poorly designed survey in an attempt to answer the question, “How do we attract and retain more teachers?”

One glaring problem I see in the report is a complete lack of thought to almost anything besides compensation. Don’t get me wrong, compensation matters, and the commission is absolutely right to consider compensation. But if you are going to examine why there are reported teacher shortages, you ought to do a better job looking for causes or kinks in the teacher pipeline. Simply surveying existing teachers about whether they’d like more money (they would) will not help us answer the most pressing questions.

What are the causes of our current teacher shortage? They are certainly varied. But one thing the commission never seemed to consider was the current hiring practices of school districts.

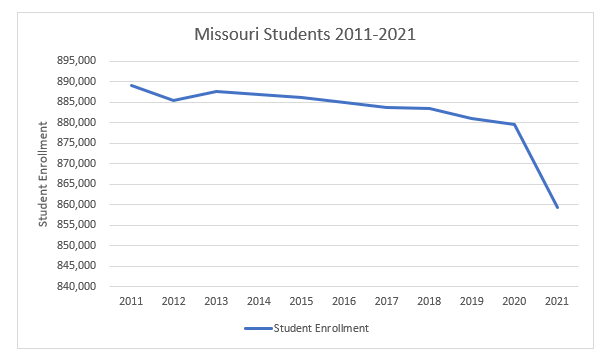

From 2011 to 2021, enrollment in Missouri public schools dropped by nearly 30,000 students. The largest drop was post-COVID, with the state losing over 20,000 students in that year alone. Nevertheless, the trend is clearly downward.

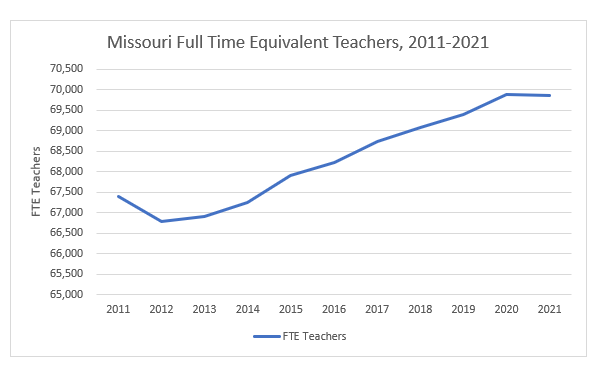

It would make sense, given that total enrollment in the state has been decreasing, to see a similar decline in the number of teachers. Fewer students, fewer teachers needed. But instead, we see the opposite happening. As enrollment drops, the state continues to add to the number of teachers. In the table below, I present the number of full-time equivalent teachers (FTE). From 2011 to 2021—the same period that the state lost 30,000 students—the state added 2,475 FTE teachers. As the state dropped 20,000 students from the rolls, it only lost 10 FTE teachers. This brings the ratio down from 13.2 students per FTE teacher in 2011 to 12.3 in 2021.

If we looked at non-teaching staff and administration, we’d likely see similar trends. Indeed, Economist Ben Scafidi found exactly this when he looked at the data from 1992 to 2015. During that time period, Missouri student enrollment increased 9% while teachers increased 28% and all other staff increased 24%. Hiring seems to be uncorrelated with trends in student enrollment.

Why didn’t the commission consider this? Why wasn’t someone willing to ask the question, “Why are we increasing the number of teachers when the number of students is dropping?”

If you want to understand the teacher shortage, this is pretty important information.