Student Loan Default in Missouri

Like many twenty-somethings, I am kept up at night—not by noisy neighbors, but by my student loan debt. I’ll be honest—I wasn’t a smart borrower.

If there is any consolation, it’s in knowing I’m not alone. In fact, more than one-fifth of borrowers have proved to be less-than-savvy higher education investors—22% have loans in default or forbearance. The consequences of default are serious, including wage garnishment and a severe hit to credit scores.

Last month, the Department of Education released data on the default rates for colleges and universities in all fifty states and abroad. Before getting into what solutions policy leaders have proposed to lessen the burden of student debt, let’s look at student loan default rates in Missouri.

The table below shows the percentage of students by type of institution who entered repayment in fiscal 2012 and had defaulted by December 2014. The default rate for public two-year institutions or community colleges was more than double that of public four-year and private four-year universities. Private four-year universities had a lower default rate than public four-year universities by 1 percentage point. Special-focus colleges like St. Louis College of Pharmacy had the lowest default rates (with the exception of the Kansas City Art Institute, which had a default rate of 10.2 percent*). To view default rates for most colleges and universities in Missouri, click here.

| Public four-year | 8.5 |

| Public two-year | 19.4 |

| Private four-year | 7.5 |

| Private two-year | 9.6 |

| Special focus | 2.6 |

The pie chart below breaks down the students in default in 2014 according to the types of institutions they attended. This figure shows that public two-year colleges produce the most student loan defaults in Missouri (this trend is also apparent nationwide).

Why? The most common defaulters are students who attend college but do not graduate. These students incur the debt, but don’t see any of the benefit, making it harder for them to pay back their loans. According to one study, the completion rate for students who start at two-year universities in Missouri is less than 40 percent. That’s a lot of students with debt and no degree. It’s a recipe for default.

To combat default, some policy leaders, including President Barack Obama, have proposed further subsidizing higher education, but that skirts the real issue. What we should really talk about is how to make college less expensive in the first place and how to help more students graduate. The state could take several steps to do that.

First, it could work with schools to promote low-cost options. States like Texas and Florida have explored ways of reducing total costs to as low as $10,000. Inexpensive degrees that students successfully complete are an antidote to default; loans (if they are even necessary) have very low payments and degrees have high benefits.

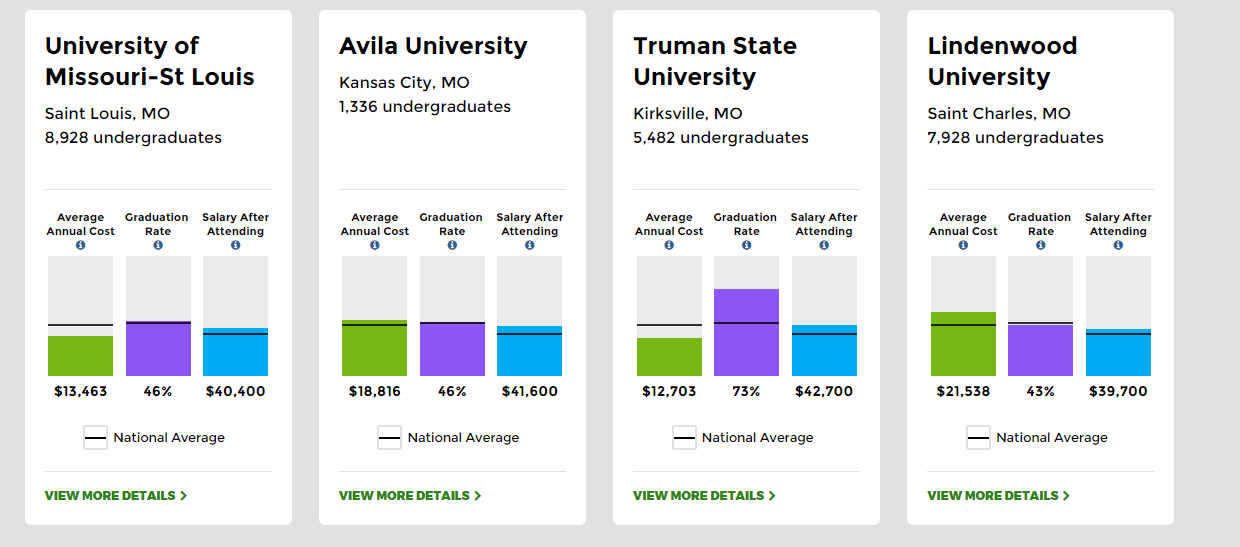

Second, the state could make both costs and benefits more transparent to potential students so they can make informed decisions and exert pressure to keep prices down. The Department of Education created the college scorecard to help students make better choices about “where to study and how to maximize their investment.” The graphs below highlight four universities in Missouri, displaying the average annual cost of attending, graduation rate, and salary after attending. The Student Right to Know Before You Go Act of 2015, an update to the Higher Education Act of 1965, was referred to a congressional committee in May and requires universities to provide more accurate and complete data.

Finally, states could force colleges to have some “skin in the game.” Under such a plan, schools would be required to pay a portion of any defaulted government loans. This would push universities to accept only students who they thought would be successful, to work with students to make it through their studies, and to help place students in jobs that will earn enough to pay back their loans.

Lower-cost options, better information, and institutions with an interest in preventing loan defaults could go a long way to helping curb debt, defaults, and the $1.3 trillion problem they create.

*The default rate for the Kansas City Art institute was originally posted as 17.1%, which was the rate reported for 2010. The 10.2% rate is correct for 2012.