Even More on Missouri Film Tax Credits

|

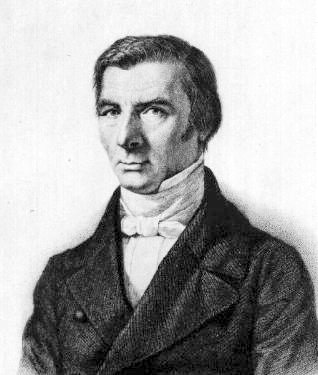

| Frédéric Bastiat |

My recent op-ed against film tax credits was published as a guest commentary in the Columbia Missourian today! As regular readers of this blog will know, it was also discussed by Steve Walsh on MissouriNet and by David Nicklaus on Mound City Money last week.

Over the weekend, I thought a lot about the arguments that were raised in favor of the film tax credit program. I’d like to take this opportunity to respond to them.

(1) The debate over the appropriateness of film tax credits is a natural application of the general principle of the parable of “The Broken Window” by Frédéric Bastiat (1850), which was later developed in Economics in One Lesson by Henry Hazlitt (1946).

I am impressed with the sheer amount of commentary generated by my recent blog posts arguing against film tax credits in Missouri. I have heard from people who worked on the Up In the Air set, professors of film, and representatives of the Missouri Film Commission, among others. In his book Economics in One Lesson, Hazlitt explicitly warns that this will happen (emphasis mine):

The group that would benefit by such policies, having such a direct interest in them, will argue for them plausibly and persistently. It will hire the best buyable minds to devote their whole time to presenting its case. And it will finally either convince the general public that its case is sound, or so befuddle it that clear thinking on the subject becomes next to impossible.

To paraphrase Bastiat and Hazlitt, government should consider ce qu’il voit et ce qu’il ne voit pas au même temps when it is deciding policy. In plain English, this means that it should consider “the big picture” instead of only one group of people when forming policy that affects everyone. Hazlitt thinks that this concept is so important that this is his “one lesson,” further reduced to a single sentence (emphasis mine):

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.

Here’s how this relates to the film tax credit program. If we only consider that which we see, ce qu’on voit, then the tax credit programs are considered to benefit everyone. The recipients of the tax credits do assuredly benefit, as they testify in their commentary (Econdiva provided an estimate that the producers of Up in the Air spent nearly $12 million in the state). Bastiat and Hazlitt warn that it is dangerous to ignore the hidden costs, ce qu’il ne voit pas, that affect everybody. Missouri should not focus solely on the benefits of bringing filmmakers to Missouri and ignore the cost of the program to taxpayers.

While certain public policies would in the long run benefit everybody (e.g., eliminating the earnings tax or commercial property tax surcharges), other policies would benefit one group only at the expense of other groups. Film tax credit programs fall into the latter category. When tax revenue is spent on film productions, taxpayers cannot spend that money in alternative ways, such as education or infrastructure; they face an opportunity cost that is equal to the amount of the subsidy.

(2) There is not enough demand in Missouri for the film industry to exist in Missouri without a considerable level of government assistance.

In their comments, both Cat Cacciatore and Dave Rutherford provided proof of this point — they both travel out of state because there isn’t enough demand for film production work in Missouri (even in today’s status quo, in which we offer a $4.5 million tax credit). If an individual decides to live in a location in which there is not enough demand for him to work full-time, why should the taxpayer have to subsidize his employment?

Let’s say that I am a trained lobster farmer and I choose to relocate to Missouri, which is at a competitive disadvantage for lobster farming because it is very far from the ocean. I have two options: (1) I can petition the government to subsidize my employment; or, (2) I can transfer my knowledge, skills, and abilities to an industry for which there is demand. I believe that the second option is better because it does not burden taxpayers.

Most Missourians work in industries that don’t have targeted tax credits. Their jobs exist because there is enough demand for them. The demand for bakers, babysitters, yoga instructors, doctors, lawyers, and free-market research analysts in Missouri is high enough so that their employers choose to pay for their jobs without government assistance.

Furthermore, if the state stops subsidizing these jobs, then it has more workers available to do other kinds of work. In the comments, Josh Smith notes that:

There is not some fixed “pool of jobs” which can only be expanded by spending tax dollars in the right way. There are many different types and amounts of work that can be done to earn a wage, specialization and trade tend to lead to a more efficient economy.

(3) The $4.5 million applies to state tax revenues, not total expenditures.

I realize that there is some confusion here, and I admit that I should have stated this more clearly in my op-ed. State tax revenues and total expenditures are different numbers. To an out-of-state production crew like Reitman’s, Missouri issues a tax credit to for up to 30 percent of the amount that they spend in state. This means that they get $3 million back if they spend $10 million in Missouri (which they can turn around and sell, because these tax credits are fungible). Given the low multiplier for the film industry (described herein), there is no way that the state would be able to recover that amount of money, whether it be through sales taxes (4.225 percent) or personal income taxes.

(4) These programs do not result in permanent economic activity.

As Sarah Brodsky points out, the purchases cited are single-time expenses (e.g., $30,000 for ice, $185,000 for set dressing items). Few permanent jobs, if any, are created when a filmmaker comes in to the state, works on a film for a finite period of time, and then goes back to California.

Additionally, according to “The Economic Impact of the UK Film Industry,” a 2007 study by Oxford Economics, the film industry has a multiplier of only 2.0. This is lower than the multiplier for the economy average, and indicates that the indirect impacts on employment and output from the film industry are not very far-reaching.

(5) Missouri should leave filmmaking to states that have a comparative advantage in it.

Why is it important that Missouri try to compete in the national or global marketplace in filmmaking? I disagree that states like Missouri should focus on developing industries for which they are at a competitive disadvantage. Missouri would be better off if it focused on the products and services that it produces best (e.g., Budweiser beer, hog farming, mining limestone, manufacturing) and then traded with other states. I agree with Josh Smith that the statement “Other states are doing it, so Missouri should too” is an insufficient reason. He observes:

If other states want to spend their residents’ tax dollars to attract filmmakers, and the result is that Missourians (1) are still able to get the benefits of the product by paying to see the movie (perhaps more cheaply if the tax credits are spent in making the film more affordable, whatever that might mean) and (2) don’t have to spend our tax money to entice the film’s production to locate here then we have a few obvious benefits.

Also, the Michigan economy is in terrible shape! Why would Missouri want to model its tax policies after Michigan’s, even when legislators there are already discussing discontinuing the program? Right now, Michigan has a unemployment rate of 15.3 percent, which is the highest in the country. (By comparison, Missouri’s current unemployment rate is 9.5 percent, which is below the national average of 10 percent). Even before the recession sharpened, Michigan had the highest rate; in September 2008, it was 8.9 percent.

As its comparative advantage, California has more sunlight than the Midwest, which allows for longer shooting hours, as well a variety of landscape types within driving distance, which can stand in for locales around the world. (Remember how Austin Powers remarked, “You know what’s remarkable? That England looks in no way like Southern California!” while driving on an “English” country road in Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me?)

(6) Subsidized industries have difficulty weaning themselves off government assistance.

When a state coddles an industry that does not have a competitive advantage (a so-called “infant industry”), the industry tends to remain dependent on that aid. Industries that are subsidized are not subject to the same competitive pressures as those that are unsubsidized, and they consequently do not have an incentive to innovate. In “The Case For Free Trade,” Milton and Rose Friedman describe some additional negative implications of these infant industries.

The infant industry argument is a smoke screen. The so-called infants never grow up. Once imposed, tariffs are seldom eliminated. Moreover, the argument is seldom used on behalf of true unborn infants that might conceivably be born and survive if given temporary protection; they have no spokesmen. It is used to justify tariffs for rather aged infants that can mount political pressure.