I attended the Missouri House Elementary and Secondary Education Committee hearing on Wednesday, January 28. The hearing covered two bills under current consideration—one on A–F letter grades for schools, and the other on literacy reform.

The committee is a diverse group with diverse views, as were the individuals giving testimony. I was expecting a lively debate and opinions from all different angles, and that’s what happened.

However, one thing I wasn’t expecting was the view expressed by several members of the committee that Missouri schools are doing just fine, or even excelling. Unfortunately, this is simply not true. Missouri schools are performing very poorly. The data on this point are publicly available and unambiguous.

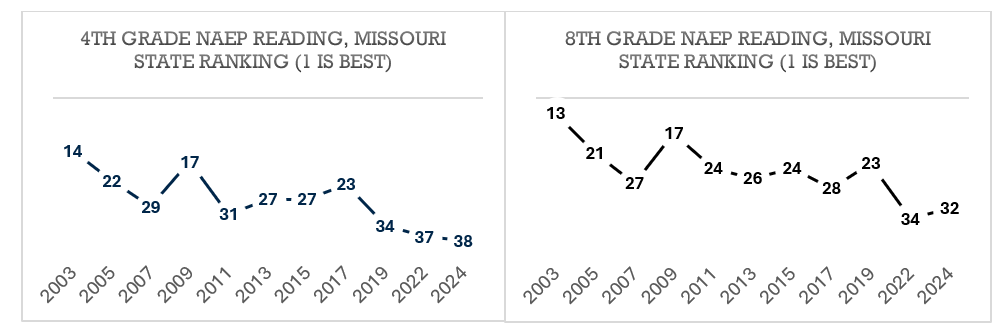

The best evidence comes from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, which is widely viewed as providing the most credible test data in the country. Here are charts showing the changes over time in Missouri’s national rank on NAEP, in 4th- and 8th-grade reading, since about the turn of the century:

(These graphs are courtesy of the Show-Me Institute’s Avery Frank.)

Our 4th-grade reading results are especially bleak—we rank 38th out of the 50 states as of 2024, whereas two decades earlier we ranked in the low twenties. Today, an alarming 42 percent of our 4th graders score Below Basic on NAEP.

Making matters worse, our ranking decline since about 2015 is in the context of generally declining test scores nationwide during this time. Our scores are declining faster than the rest of a declining nation.

The only reason not to be worried about this is if you don’t believe these tests tell us anything important. On this point, there is overwhelming evidence that NAEP—and standardized tests more broadly—are highly predictive of consequential long-term outcomes. There are hundreds—maybe thousands—of articles that show a link between standardized test performance and later life outcomes.

In fact, just last year a high-quality study on NAEP scores found the following: “More recent birth cohorts in states with large increases in NAEP math achievement enjoyed higher incomes, improved educational attainment, and declines in teen motherhood, incarceration, and arrest rates compared to those in states with smaller increases.” Whatever outcome you care about for our children, NAEP scores predict it. (If you’re interested in recent, related evidence from Missouri’s MAP test, see here.)

Our declining test scores should concern all of us. Whether the committee members recognize it or not, under their watch and the watches of their predecessors over the last decade plus, Missouri’s academic performance has been declining. An overwhelming body of research tells us the decline will have real consequences for our children, and ultimately this will have real consequences for the future of our state.

I recognize we won’t all agree on the solutions, but it became apparent during the hearing that we don’t even agree on the problem. I encourage skeptics of my message—especially members of the education committee, who have the power to make change—to look at the data themselves. Putting our heads in the sand will not make the consequences any less dire down the road.

(If you’d like to see specific examples to get a sense of the kinds of NAEP questions Missouri children can and cannot answer correctly, see an earlier post here.)