Entrepreneurship in Missouri, Part 3: The Startup Environment

This series on entrepreneurship has highlighted the fact that the percentage of workers in startups is at its lowest level in Missouri in 20 years. In fact, job growth from startups has been floundering throughout the seven years since the recession ended. In this last blog in the series, we will review two partial but significant explanations of declining startup growth in Missouri, Kansas City, and Saint Louis: net population flows and business consolidations. The research on the relationship between these two factors and entrepreneurship comes from Ian Hathaway from Ennsyte Economics and Robert E. Litan from the Brookings Institution.

Hathaway and Litan found that the more population growth an area experiences, the more likely the area is to see startup activity. Tax migration flows show that Missouri has seen a net outflow of people since 2011, driven by larger outflows from Kansas City and Saint Louis. While it is still possible for Missouri, Kansas City, and Saint Louis to grow in entrepreneurial activity despite a net migration loss, Hathaway and Litan find that those areas with fast and positive migration have more entrepreneurial activity. Unfortunately, that migration isn't really happening in the Show-Me State.

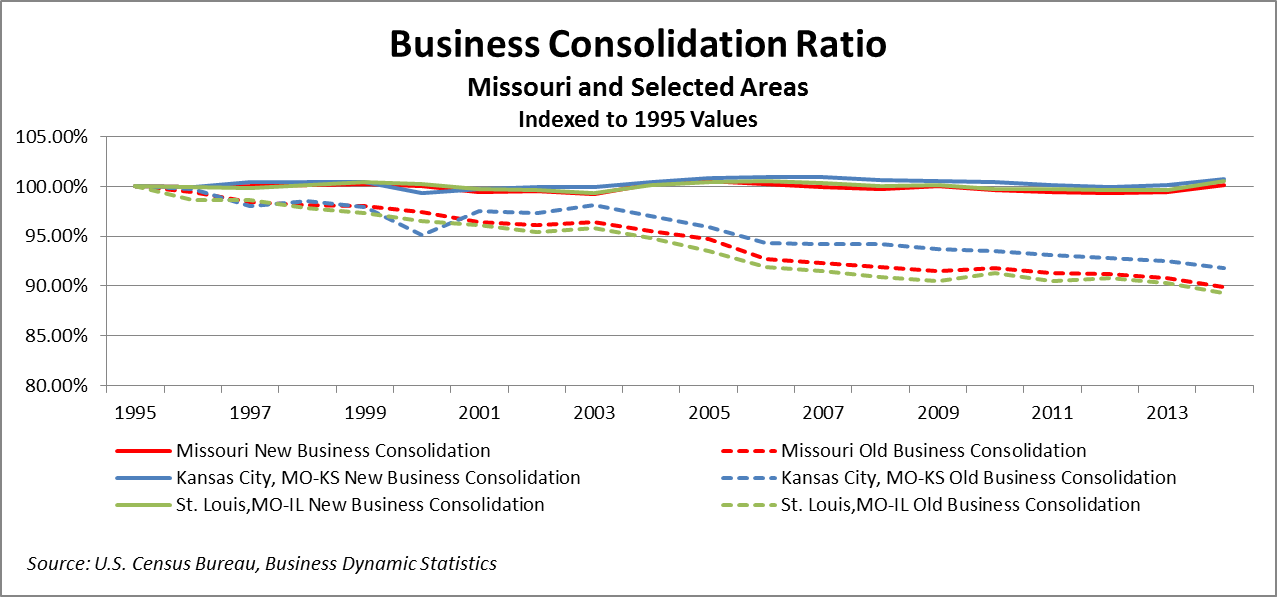

The business consolidation rate that Hathaway and Litan use is calculated by dividing the number of firms (e.g., Home Depot) by the number of establishments (individual Home Depot stores) within an area. Business consolidation can be a good indicator of business cost pressures, because as the costs of maintaining a firm’s establishments increase, business owners may decide to close or consolidate establishments. Therefore, a falling business consolidation ratio (i.e., each firm operates more establishments) indicates that overall, firms are expanding. On the other hand, a rising ratio indicates that firms are contracting their business operations.

The business consolidation ratio for older firms in Missouri seems to be declining over time, which may suggest that, on aggregate, these businesses are able to manage their costs of doing business and are expanding. For startups, however, business consolidation has remained flat, suggesting cost pressures may continue to be a problem for these new or relatively new companies. The chart below captures these trends.

Remember: the downward slope of a line is a good thing, and reflects better conditions for a firm’s expansion. Policymakers should take a closer look into the startup environment, because review of Missouri, Kansas City, and Saint Louis shows that startups aren’t doing nearly as well as older and more established firms in terms of expansion. Over the last 10 years or so, the gap between established firms and startups has grown without pause.

How can Missouri policy help foster an environment in which entrepreneurs not only want to operate here, but also enjoy enough success that they are able to expand their operations? My first post in this series outlined how Kansas City businesses are enticed to move to lower-tax environments, indicating that tax policy might be a good place for policymakers to start. In addition, with Missouri ranked 29th in least-burdensome regulations for startups, (see page 49)., regulatory reform is another area where improvement would be welcome.